From the moment we wake up in the morning until the moment we fall asleep we are constantly barraged with sensory stimuli. The smell of coffee, the buzzing of the alarm, the dinging of email alerts, yet somehow, we identify the salient sensory stimuli and ignore the rest in order to generate an appropriate behavioral response each moment. Which stimuli we identify to be salient could depend on additional factors such as our external and internal environments. For example, after a good night’s sleep, coffee might not be considered a salient stimulus. If, however, you were a physician on call all evening, the smell of coffee might become highly salient the very next day. In other words, adaptive behavior requires the ability to (1) discriminate salient sensory stimuli from background noise, (2) assign valence (attractive or aversive value) to salient sensory stimuli, (3) integrate environmental and internal physiological state, and (4) generate appropriate behavioral output.

Although we and other organisms rely on constant integration and updating of our internal and external environment, we know little about how the brain supports this integration. Work in my lab aims to identify how the brain can accomplish step three: integration of stimuli to drive contextually appropriate behavior. The complexity of the mammalian nervous system precludes fully understanding the processes underlying multisensory integration. In contrast, the fly must also follow the steps outlined above to generate behaviors that support its survival. However, due to the small size of the fly brain along with the availability of an incredibly diverse set of scientific tools, we are able to identity single genes, neurons, and circuits that underlie how a brain can make a decision to generate behavior that will promote survival in a variety of contexts.

My lab utilizes a multifaceted approach: (1) genetic manipulation to allow control over specific neural pathways, (2) visual and olfactory ‘virtual-reality’ flight simulators2,3 to measure sensory motor integration that drives adaptive behavior, (3) optogenetic manipulations4 to activate desired neurons in awake and behaving animals, and (4) in-vivo two photon calcium imaging as an indicator of neuronal activity.

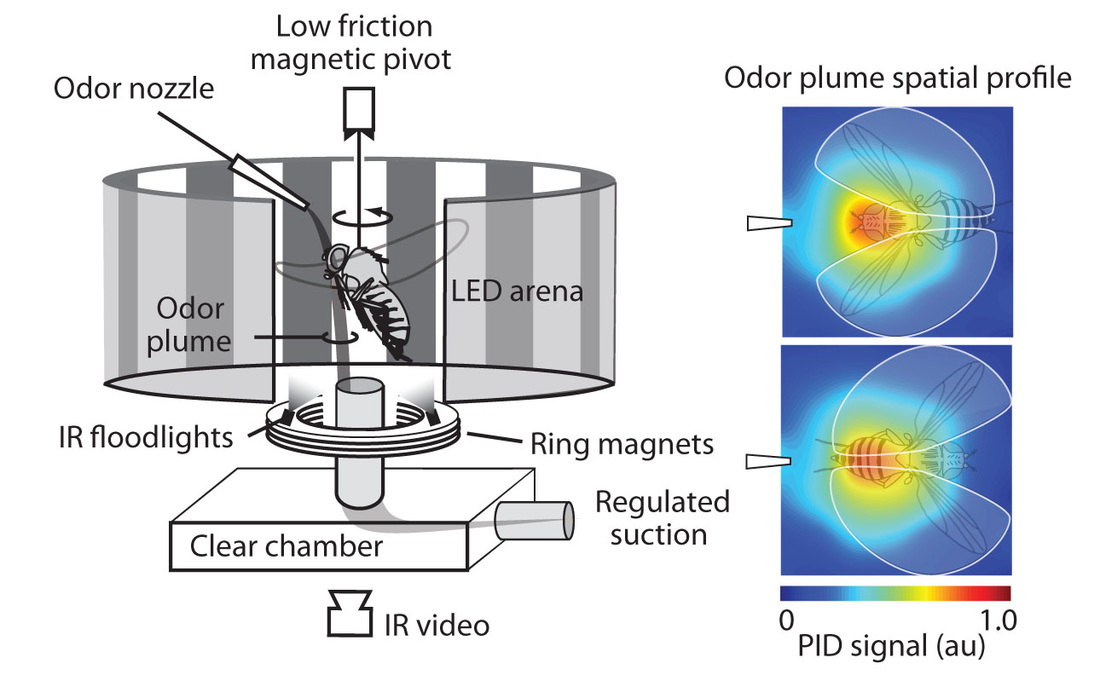

As a postdoctoral fellow in Mark Frye’s lab at UCLA and now in my own lab, I investigate the way in which an organism interacts with its environment to generate an appropriate behavioral output. This work explores how stimulus state (valence), behavioral state (walking vs. flying), and internal state affect the behavioral transformation of sensory information. I make use of two sophisticated behavioral assays for olfactory behavior: a magnetic arena in which a tethered fly can actively rotate within a spatially discrete odor plume against the backdrop of a fixed electronic visual display (Figure 1) and a second system in which a rigidly tethered fly within a fixed odor plume can actively steer the visual panorama. These ‘virtual reality’ visual and olfactory analysis systems allow for precise delivery of multiple stimuli simultaneously and quantitative measures of behavioral performance from wild-type and genetically altered animals. Major findings from my work are summarized below.

Although we and other organisms rely on constant integration and updating of our internal and external environment, we know little about how the brain supports this integration. Work in my lab aims to identify how the brain can accomplish step three: integration of stimuli to drive contextually appropriate behavior. The complexity of the mammalian nervous system precludes fully understanding the processes underlying multisensory integration. In contrast, the fly must also follow the steps outlined above to generate behaviors that support its survival. However, due to the small size of the fly brain along with the availability of an incredibly diverse set of scientific tools, we are able to identity single genes, neurons, and circuits that underlie how a brain can make a decision to generate behavior that will promote survival in a variety of contexts.

My lab utilizes a multifaceted approach: (1) genetic manipulation to allow control over specific neural pathways, (2) visual and olfactory ‘virtual-reality’ flight simulators2,3 to measure sensory motor integration that drives adaptive behavior, (3) optogenetic manipulations4 to activate desired neurons in awake and behaving animals, and (4) in-vivo two photon calcium imaging as an indicator of neuronal activity.

As a postdoctoral fellow in Mark Frye’s lab at UCLA and now in my own lab, I investigate the way in which an organism interacts with its environment to generate an appropriate behavioral output. This work explores how stimulus state (valence), behavioral state (walking vs. flying), and internal state affect the behavioral transformation of sensory information. I make use of two sophisticated behavioral assays for olfactory behavior: a magnetic arena in which a tethered fly can actively rotate within a spatially discrete odor plume against the backdrop of a fixed electronic visual display (Figure 1) and a second system in which a rigidly tethered fly within a fixed odor plume can actively steer the visual panorama. These ‘virtual reality’ visual and olfactory analysis systems allow for precise delivery of multiple stimuli simultaneously and quantitative measures of behavioral performance from wild-type and genetically altered animals. Major findings from my work are summarized below.

Figure 1 (left panel): A fly is tethered to a pin and suspended in a magnetic tether arena where it can freely rotate in the yaw plane. Panels of light emitting diodes surround the arena and display high contrast stationary and moving visual patterns (not shown) used to orient each fly in a standard starting orientation and provide visual feedback during self-motion. The odor port at 0° delivers a narrow stream of odor (indicated in green) that flows over the fly’s head and is drawn downward and away by a vacuum through the aperture of the ring magnet. The angular heading of the fly is tracked by infrared video. (right panel): The spatial cross-section of the plume, at the horizontal plane of the antennae, was measured for ethanol tracer with a miniature-photoionization detector, averaged over 11 repeated measurements across a 9x9 grid, smoothed with piecewise linear interpolation, normalized to the maximum ionization amplitude, and mapped onto a standard color scale (blue = 0, red = 1) (Wasserman et al., 2013 Current Biology).

Research Highlights

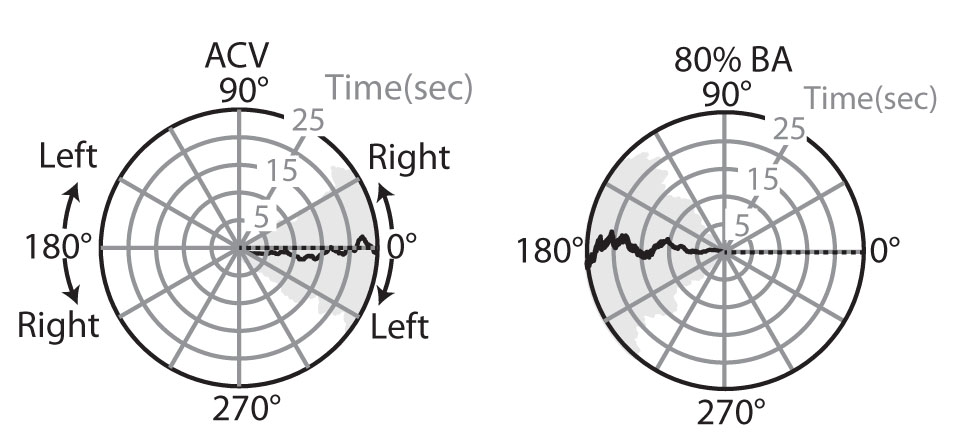

(1) Flies actively locate and continuously ‘anti-track’ an aversive odor plume using the same sensorimotor transformations that underlie tracking an attractive odor in-flight. The in-flight behavioral response to attractive odor has been well documented using a magnetic tether flight simulator [2]. As I began my postdoc little was known about the mechanisms driving in-flight escape or avoidance behaviors, which are equally critical for survival. To examine the similarities and differences in the algorithms by which the brain transforms the valence of an odor signal, I compared the in-flight behavioral responses to spatially restricted attractive and aversive odor plumes. I found that flies steer in the direction exactly opposite an aversive odor source, demonstrating strong olfactory sensitivity and active “anti-tracking” (Wasserman et al. 2012, J. Exp. Biol.). Tracking an appetitive odorant and anti-tracking an aversive odorant seems to be achieved by the same sensorimotor transformation, yet the sign of the gradient tracking is simply inverted for a negative valence odorant by comparison to a positive valence one.

Figure 2. Flies actively track and anti-track an attractive and aversive odorant, respectively. Polar plots of mean heading in response to 100% ACV (left) and 80% benzaldehyde (BA, right). Black line indicates mean heading trajectory, shaded grey area represents the standard error of the mean (SEM). Odor plume indicated by dashed black line. n > 70 flies. (Wasserman et al. 2012, J. Exp. Biol.)

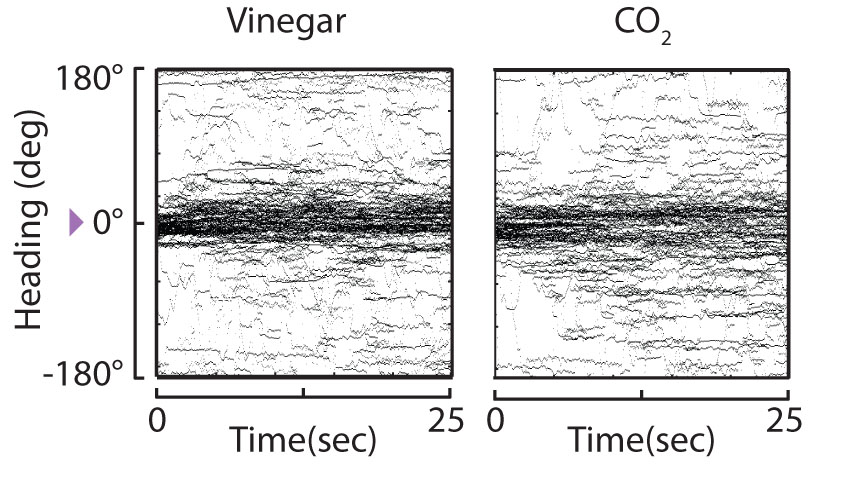

(2) The behavioral state (walking vs. flying) of the fly alters the valance it assigns an olfactory stimulus. Carbon dioxide (CO2) has long been known to act as an attractive host-identifying odor to mosquitoes but somewhat surprisingly, has always yielded an aversive response from D. melanogaster. To date, all experiments investigating the response of D. melanogaster to CO2 have been performed using walking flies. I examined the in-flight response of fruit flies to CO2 and showed that while flies avoid CO2 on foot, they seek out and track a CO2 plume in flight. Additionally, I have shown that in-flight attraction to CO2 requires recruitment of odor and acid sensing pathways that gain sensitivity to CO2 in-flight via increased levels of octopamine in the fly brain (Wasserman et al., 2013 Current Biology). I am currently elucidating the molecular and circuit mechanisms by which the valence of CO2 switches in a behavioral state-dependent manner using genetic, behavioral, and calcium imaging techniques.

(2) The behavioral state (walking vs. flying) of the fly alters the valance it assigns an olfactory stimulus. Carbon dioxide (CO2) has long been known to act as an attractive host-identifying odor to mosquitoes but somewhat surprisingly, has always yielded an aversive response from D. melanogaster. To date, all experiments investigating the response of D. melanogaster to CO2 have been performed using walking flies. I examined the in-flight response of fruit flies to CO2 and showed that while flies avoid CO2 on foot, they seek out and track a CO2 plume in flight. Additionally, I have shown that in-flight attraction to CO2 requires recruitment of odor and acid sensing pathways that gain sensitivity to CO2 in-flight via increased levels of octopamine in the fly brain (Wasserman et al., 2013 Current Biology). I am currently elucidating the molecular and circuit mechanisms by which the valence of CO2 switches in a behavioral state-dependent manner using genetic, behavioral, and calcium imaging techniques.

Figure 3. CO2is an attractive stimulus to flies in flight. Tethered wild-type (WT) flies track apple cider vinegar (vinegar, left panel) and carbon dioxide (CO2, right panel). Within-subjects design was used, heading trajectories of all individuals are plotted for a continuous odor plume of vinegar, n = 87 trials and CO2, n = 78 trials. Heading distributions are not significantly different from each other (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, P=0.9448) (Wasserman et al., 2013 Current Biology).

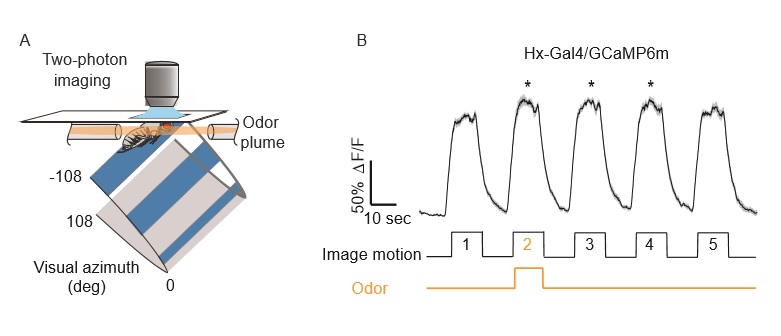

(3) Olfactory neuromodulation of motion vision circuitry. It has been shown in flies and humans that attention to one stimulus can translate to a heightened attention towards a secondary stimulus, and thus enhance multisensory integration. The fly depends on wide-field motion vision to strengthen odor localization and plume tracking of odorants. In turn, these odorants increase the fidelity of visual behavior. Using 2-photon calcium imaging in awake and behaving flies (Figure 4), I have shown an increase in the response amplitude of a novel group of motion detecting neurons to wide-field motion in the presence of an attractive odorant and revealed that this enhanced response requires trafficking of synaptic vesicles in octopaminergic neurons. (Wasserman and Aptekar et al., 2015 Current Biology)

(3) Olfactory neuromodulation of motion vision circuitry. It has been shown in flies and humans that attention to one stimulus can translate to a heightened attention towards a secondary stimulus, and thus enhance multisensory integration. The fly depends on wide-field motion vision to strengthen odor localization and plume tracking of odorants. In turn, these odorants increase the fidelity of visual behavior. Using 2-photon calcium imaging in awake and behaving flies (Figure 4), I have shown an increase in the response amplitude of a novel group of motion detecting neurons to wide-field motion in the presence of an attractive odorant and revealed that this enhanced response requires trafficking of synaptic vesicles in octopaminergic neurons. (Wasserman and Aptekar et al., 2015 Current Biology)

Figure 4. Odor modulates Hx activity. (A) Schematic of LED arena display and odor delivery within the imaging apparatus. (B) Intracellular calcium responses to visual motion by Hx neurons expressing GCaMP6m. Mean ∆F/F ± 1 SEM is shown. * p < 0.05, rank-sum test on peak response amplitude compared between epoch one (prior to odor stimulation) and each following epoch, n = 13 animals.

(4) Geographically isolated species of fruit flies assign different values to the same visual stimulus. We all have strong odor preferences that are linked to our environment. For example, you may smell oatmeal cookies baking as you walk by a bakery and immediately smile at the pleasant smell you remember coming from your grandmother’s kitchen and stop inside to pick up a cookie. Interestingly, fruit flies develop these same odor preferences based upon the food sources in their environment. It is known that geographically isolated populations of fruit flies have odor preferences that correspond to local features of their environment, however little work has investigated whether certain environments could also drive changes in the value assigned to visual features. In other words, like smell, could the features that we see in our environment influence how we respond to visual cues? Recent work from my lab reveals that indeed, external environmental features can modulate the first step of generating adaptive behavior by altering what sensory stimuli are deemed salient or important to pay attention to. Comparing fruit flies native to forested areas (D. melanogaster) with those from the Mojave Desert (D. mojavensis), we were the first to report that these two geographically isolated species of fruit flies assign different values to the same visual stimulus. Emily Park (’18) first-authored a paper with her findings (Park and Wasserman, 2018 Current Biology).